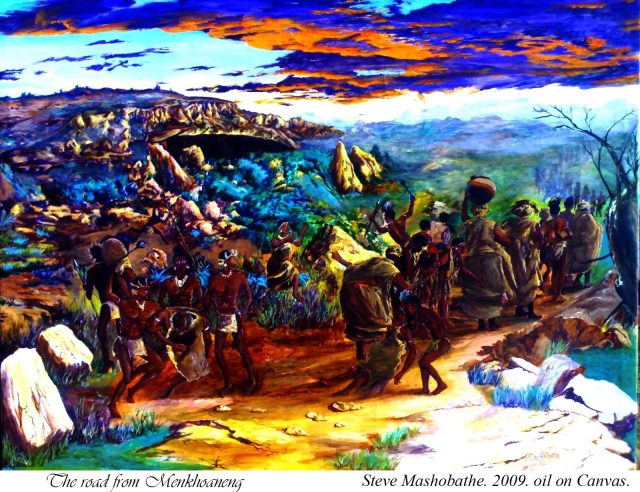

The Journey that Built a Nation – Menkhoaneng to Thaba-Bosiu

Writes Professor Tefetso Mothibe

In 2024, Lesotho will celebrate two hundred years since its founding by Morena Moshoeshoe I. It is an important year as it marks the bicentenary of the existence of the Basotho state and nation, marked by the exodus of Moshoeshoe and his followers from Menkhoaneng to Thaba-Bosiu. This historic relocation to Thaba-Bosiu is the turning point in the formation of the Basotho Nation. It is even more important because we acknowledge, appreciate, recognise and promote the positive and constructive role played by Morena Moshoeshoe I, a humane and intelligent man and a skillful and far-sighted patriot who despite serious odds, managed to build the Basotho nation in the midst of chaos and warfare.

It is said that Moshoeshoe and his people arrived in the late afternoon near conical Qiloane hill and it took them a long time to negotiate their way up the mountain. In the morning when they retraced their steps, they realised that the mountain was not as high as it had appeared during the night. They remarked that ‘Ke thaba ha e le bosiu’ which explains how the mountain fortress got its name in the short form, Thaba-Bosiu. Thaba-Bosiu was and still is, the citadel of Basotho. Moshoeshoe himself called the mountain his mother and the mother of all his people. It was the Promised Land for Basotho.

Born in 1786, Moshoeshoe was a member of a minor chiefly family of the Bakoena lineage and his parents, Mokhachane and Kholu, named him Lepoqo (Dispute). He later earned the name of Moshoeshoe as a result of his bravery and success as a cattle raider. Moshoeshoe seems to have harboured an ambition for greatness and was determined to achieve this by means that included violence, instilling fear in others, intolerance and impatience with the tardy execution of his orders. Indeed, so intolerant was the young Lepoqo that he is reported to have on one occasion killed five of his followers – some for the small offence of milking his favourite cow and others for the slow implementation of his orders. However, a meeting with and teachings of Morena Mohlomi, the son of Monyane, who was a doctor, traveller, sage, philosopher and mystic changed all this. Mohlomi is said to have advised Moshoeshoe that the best way to achieve his ambition of becoming Morena was to behave in a humane and intelligent way. He is reported to have said to Moshoeshoe, “Someday, in all probability, thou wilt be called to govern men. When thou shalt sit in judgment, let thy decisions be just. The law knows no one as a poor man.”[1] Mohlomi emphasized the value of peaceful negotiations and fairness in dealing with other people. He was reported to have loved the saying, “it pays better to fight the corn than to whet the spear.”[2]

Like all other young men of his era, the time came for Moshoeshoe to leave his parents’ house to establish his own homestead. As the first son of a minor chief, in his case, this included founding his own village with his followers away from his father’s village of Menkhoaneng. In readiness for this, he began to gather around him a core group of followers made up of his age-mates and added to it groups such as Bafokeng of Ntsukunyane, Bafokeng of Ramohau and influential individuals like his maternal uncle Rats’iu. There were at least two ways, by which Moshoeshoe brought other chiefdoms and lineages under his chiefdom. He used the policy of “subordination and cooption, “and direct attacks and defeat of those who opposed him. Such was the fate of Basia of Shekeshe and Bafokeng of Makara.

Like all other young men of his era, the time came for Moshoeshoe to leave his parents’ house to establish his own homestead. As the first son of a minor chief, in his case, this included founding his own village with his followers away from his father’s village of Menkhoaneng. In readiness for this, he began to gather around him a core group of followers made up of his age-mates and added to it groups such as Bafokeng of Ntsukunyane, Bafokeng of Ramohau and influential individuals like his maternal uncle Rats’iu. There were at least two ways, by which Moshoeshoe brought other chiefdoms and lineages under his chiefdom. He used the policy of “subordination and cooption, “and direct attacks and defeat of those who opposed him. Such was the fate of Basia of Shekeshe and Bafokeng of Makara.

Around 1820, Matiwane of AmaNgwane attacked some chiefdoms in Lesotho. These attacks awakened Moshoeshoe to the fact that he needed a safer place to safeguard and expand his young chiefdom. Then, at the age of about 34, he, together with his followers, moved away from his birthplace of Menkhoaneng to Botha-Bothe Mountain. There he adopted a new policy of striking alliances with other chiefs to enlarge and safeguard his chiefdom. One such alliance was that between Moshoeshoe and Lethole, chief of Makhoakhoa where, according to Thompson, under this alliance “each ruler would remain autonomous but cooperate against aggressors and in doing so, they would act under the leadership of Moshoeshoe.”[3] This strategy of alliances would be pursued by Moshoeshoe in the 1840s and the 1850s when he struck alliances with Moletsane of Bataung and Moorosi of Baphuthi while the Batlokoa were subjugated in the 1850s.

The intensity of the Lifaqane, violent upheavals that unleashed a train of refugee-chiefdoms attacking and fleeing from one another, of the 1820s led to the destruction of food, lives and property. The Botha-Bothe Mountain proved not to be such a secure fortress and constant attacks on it, especially the three months ‘siege by Sekonyela of the Batlokoa assisted by his uncle and Nkhahle of the other main branch of Batlokoa, led Moshoeshoe to look for a safer place where he could settle with his followers. He is reported to have sent his half-brother, Mohale to inspect the land south that he learnt had not been so badly devastated by wars which contained a mountain which would make an excellent fortress. Mohale had returned and confirmed that he had indeed found a defensible mountain.

Around June or July 1824,mid-winter and bitterly cold, Moshoeshoe and his now large following, (though difficult to estimate its number), including their livestock and portable

[1] As quoted in L. Thompson, Survival in Two Worlds Moshoeshoe of Lesotho, 1786-1870. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1975, p. 26.

[2] T.Arbousset and F. Daumas, Narrative of an Exploratory Tour to the North-East of the Colony of Cape of Good Hope, Cape Town: A.S. Robertson, 1846, p.378.

[3] L. Thompson, Survival in Two Worlds, p. 39.

possessions, is reported to have taken an important decision to move to Thaba-Bosiu. It is also reported that the trip took seventy miles on foot and three nights to complete through a mountainous country infested with cannibals. On the second day of the trip as they climbed the Lipetu pass, old people, pregnant women and young children who were moving slowly and were last of the group, were attacked by a band of cannibals led by Rakotsoane. In this attack, some of the women and children, including Moshoeshoe’s grandfather, Peete, were killed and eaten while the majority were rescued by Moshoeshoe’s warriors. Instead of ordering the killing of these cannibals when Rakotsoane confessed to the crime upon being caught, Moshoeshoe not only strongly opposed his advisors who wanted them killed for such a heinous crime but had an ox slaughtered and purification medicines prepared and applied on the cannibals’ tummies to cleanse them of the sacrilege of eating human flesh and as he would say, to preserve these symbols of his grandfather’s burial. Moshoeshoe went further to present the cannibals with mafisa[1] cattle and land to grow crops, decreeing that they should permanently give up cannibalism.

possessions, is reported to have taken an important decision to move to Thaba-Bosiu. It is also reported that the trip took seventy miles on foot and three nights to complete through a mountainous country infested with cannibals. On the second day of the trip as they climbed the Lipetu pass, old people, pregnant women and young children who were moving slowly and were last of the group, were attacked by a band of cannibals led by Rakotsoane. In this attack, some of the women and children, including Moshoeshoe’s grandfather, Peete, were killed and eaten while the majority were rescued by Moshoeshoe’s warriors. Instead of ordering the killing of these cannibals when Rakotsoane confessed to the crime upon being caught, Moshoeshoe not only strongly opposed his advisors who wanted them killed for such a heinous crime but had an ox slaughtered and purification medicines prepared and applied on the cannibals’ tummies to cleanse them of the sacrilege of eating human flesh and as he would say, to preserve these symbols of his grandfather’s burial. Moshoeshoe went further to present the cannibals with mafisa[1] cattle and land to grow crops, decreeing that they should permanently give up cannibalism.

As soon as they reached the mountain that was recommended by Mohale, Moshoeshoe is reported to have placed men to guard the approximately six passes[2] and did what was necessary to protect his people from human enemies and malignant spirits. “Stones [were] smeared with medicine from his lenaka, (a horn, preferably a rhinoceros horn, containing a potion composed of a mixture of vegetable and animal materials and human flesh), were driven into the ground at the tops of the passes and on the sites he selected for his lekhotla, his cattle kraal, and his personal hut.”[3] The pass next to his village became known as the Khubelu, the Red Pass, because of the red dolerite in its bed.[4]

Thaba-Bosiu provided a much better fortress than Botha-Bothe did. It proved to be an excellent defensive position, with steep sides and only six natural passes to the top. In addition, the Basotho defensive fortifications and their rolling boulders down upon invaders prevented any enemy from ever capturing the plateau. The eight natural springs allowed Moshoeshoe and his followers to survive long sieges. African and European invaders such as Amangwane of Mpangazitha in the 1820s and 1830s and the Boer Louis Wepener in the 1860s, who was the only enemy ever to reach the top of the mountain, were unable to capture the plateau. Legend has it also that Thaba-Bosiu which literally translates as

[1] Cattle in Sesotho society were of prime importance both as a means of production and reproduction in the form of acquision of wives. Under mafisa system, the person loaned the cattle enjoyed use rights. He was allowed to consume the dairy products and, after the introduction of the plough, to use the oxen as draught animals. Occasionally, he was allowed to slaughter an animal that was too old for productive purposes. The one who loaned the cattle retained the ownership of the cattle and their issue and had a right of inspection over such cattle any time he wished.

[2] The names of these passes were Khubelu or Rafutho, Ramasele, Maebeng, RaEbe, and Mokhachane .

[3] L. Thompson, Survival in Two Worlds, p.43.

[4] P. Sanders, Moshoeshoe, Chief of the Sotho, London: Heinemann,1975, p.35.

Mountain at Night explains why the invaders were unable to capture it because it grew at night.

For his protected position on top of Thaba –Bosiu, Moshoeshoe employed political and socio- economic strategies to build his nation. Politically, he continued and refined his strategies of cooptation and military subjugation of other chiefdoms. Examples are that in 1825, his half-brother, Mohale, forced Baphuthi to submit to Moshoeshoe’s authority after they lost almost all their cattle to the Abathembu. In the 1820s, Bataung became subjects of Moshoeshoe after he placed his other half-brother, Mopeli, over them. In 1853 after years of rivalry and struggle for supremacy in the Mohokare valley, Moshoeshoe himself attacked, defeated and subjugated Sekonyela and his Batlokoa under his rule.

For his protected position on top of Thaba –Bosiu, Moshoeshoe employed political and socio- economic strategies to build his nation. Politically, he continued and refined his strategies of cooptation and military subjugation of other chiefdoms. Examples are that in 1825, his half-brother, Mohale, forced Baphuthi to submit to Moshoeshoe’s authority after they lost almost all their cattle to the Abathembu. In the 1820s, Bataung became subjects of Moshoeshoe after he placed his other half-brother, Mopeli, over them. In 1853 after years of rivalry and struggle for supremacy in the Mohokare valley, Moshoeshoe himself attacked, defeated and subjugated Sekonyela and his Batlokoa under his rule.

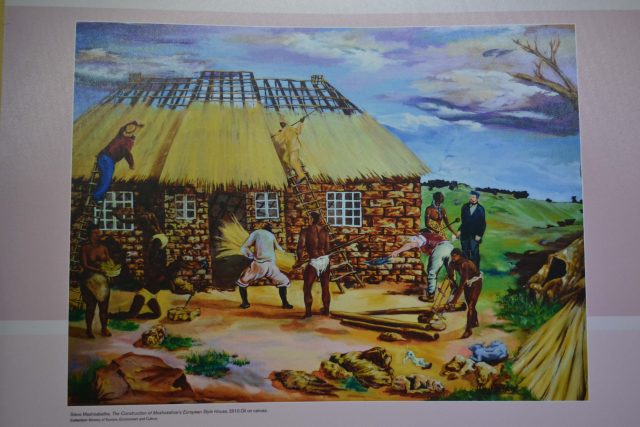

Apart from political strategies, Moshoeshoe also used economic and social strategies to build the Basotho nation. Central to the forging and consolidation of his rile and the emergence of the Basotho state was his control over the herds of cattle which were raided from neighbouring chiefdoms and their distribution through a patronage system of mafisa. By 1839, Moshoeshoe had distributed most of his estimated 20000 herds of cattle as mafisa.[1] The provision of mafisa created a social as well as economic dependency in the form of a patron-client relationship. This dependency in turn had political implications between a chief and his subjects because the ‘beneficiary’ was expected to owe allegiance to his chief. This meant that the stability of chiefdom and the size of a chief’s following depended on the number of his herds and how well he used these to create patron-client relationships.

Marriage was another important instrument in the nation-building process. Moshoeshoe married many wives from the families of different chiefs and allies and in the process bore many children. Through his many daughters, he was able to acquire a lot of cattle from the custom of bohali (bridewealth) which he in turn used as mafisa. In 1833 Casalis thought that Moshoeshoe had thirty wives.[2]

By 1833 Moshoeshoe’s chiefdom was the largest and most powerful in the Mohokare valley, and as early as 1834, Moshoeshoe was recognised by the British at the Cape as the “…sovereign ruler of his nation and a leader of remarkable talent.”[3] At the same time (1833), the missionaries estimated that the kingdom of Lesotho had about 25 000 followers most of whom were survivors of lifaqane. Thaba-Bosiu was the capital and was estimated to have about 2 000 people on and around the mountain.[4] This was the pre-eminent settlement where Mokhachane, Moshoeshoe, his wives, children, some of his matona (ministers), bahlanka (clientship), herbalists, rainmakers, diviners, praise-singers, town criers, personal

[1] J. Backhouse, A Narrative of a Visit to the Mauritius and South Africa, London: Hamilton Adams, 1844, p.375.

[2] As quoted in P. Sanders, Moshoeshoe, p.126.

[3] S. Gill, A Short History of Lesotho, p.88.

[4] Quoted in L. Thompson, Survival in Two Worlds, pp.60 and 64.

attendants and herdsmen lived.[1] Moshoeshoe ruled this core area directly with the help of Masopha, his third son in the first house of ‘Mamohato, his first wife.

During the remaining 46 years of Moshoeshoe’s life since 1824, Thaba- Bosiu became not only the political center of Basotho nation but the center of organised resistance to European encroachment and invasion. European invaders, the British in 1852, and the Boers of the Orange Free State (1858-1868) had no more success in storming Moshoeshoe’s mountain. During a siege of Thaba-Bosiu on the 15 August 1865, the Boer leader, Louis Wepener made it to the top of Khubelu Pass only to be struck down by a bullet. Wepener is the only enemy ever to reach the top of the mountain, and for this reason, he has remained linked to it as Khubelu Pass is also known as Wepener’s Pass.

[1] Thompson, Survival, p.61.