Makhoarane Precinct, the melting pot of Basotho culture and the preservation of the Royal Heritage.

Writes Stephen Gill

Introduction: Makhoarane as a site of cultural ferment

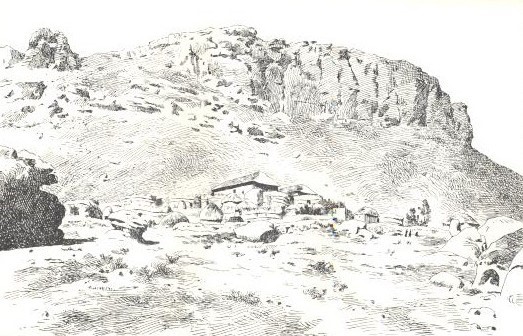

In mid-1833, just nine years after Moshoeshoe and his people established themselves at Thaba-Bosiu, the citadel and ‘mother’ of the Basotho nation, from which Moshoeshoe was able to expand many-fold the territory under his suzerainty, ‘teachers of peace’ arrived to add a new element to the experiment in nation-building. Invited by Moshoeshoe himself, who was desirous of concluding an alliance or partnership with them, these young missionaries of the Gospel were guided to the south by the monarch himself. Makhoarane was selected as the most suitable location, well-watered, with good soil and abundant wood. A small settlement arose there which the missionaries christened ‘Morija’ (The Lord Will Provide).

Makhoarane is a long, curved plateau that rises 400 metres above the plain. The area had previously been home to the Bushmen, and then from the 1600s, the Mapetla or Pioneers (Amatsetza, from the Zizi), the first mixed farming peoples to settle the Caledon River valley. Temporarily devoid of population because of the upheavals of the Lifaqane, Makhoarane now became home not only to the French Protestant missionaries, but also to the cohorts of Letsie and Molapo, Moshoeshoe’s two senior sons, and their maternal uncle, Matete.

Makhoarane is a long, curved plateau that rises 400 metres above the plain. The area had previously been home to the Bushmen, and then from the 1600s, the Mapetla or Pioneers (Amatsetza, from the Zizi), the first mixed farming peoples to settle the Caledon River valley. Temporarily devoid of population because of the upheavals of the Lifaqane, Makhoarane now became home not only to the French Protestant missionaries, but also to the cohorts of Letsie and Molapo, Moshoeshoe’s two senior sons, and their maternal uncle, Matete.

From the very beginning, it was Moshoeshoe’s intention to see what would emerge from the interface between his people and the missionaries, who dedicated themselves to the nation: “In order to prove to our new friends the firmness of our convictions . . . and the purity of our intentions, we offered to establish ourselves definitely in their midst, and to share their lot, whatever it might be”.[1]

[1] Eugene Casalis, My Life in Basutoland, J. Brierley translation, facsimile reprint of the 1889 edition, (Cape Town: C. Struik, 1971), p. 183.

True to their word, Casalis, Arbousset and Gosselin, as well as their wives and other colleagues who followed, both at Morija and at additional sites, worked tirelessly to build the nation through the rejuvenating work of the Gospel. They also worked to enhance local communities through literacy, various crafts and other educational initiatives, as well as Western medicine and forms of healing, new crops, fruit trees, domesticated cats, and a range of technologies. Casalis in particular became an advisor to Moshoeshoe on diplomatic issues, while Arbousset developed local leaders in the church and embryonic schools through his ‘Society of Evangelists’.

Basotho sifted and adapted these different initiatives and experiences, comparing and contrasting these with their own traditions and felt needs. As such, a range of syntheses emerged as culture became in some regards more pluralistic. Much ferment arose in the contestation of worldviews and the personal encounters that took place, leading as well to new creative expressions. So too, the ‘baruti ba khotso’ endured war, disease, draught, locusts and other challenges together with their followers and the nation, to the point that they, though relatively few in number, became one of the pillars of nationhood even during the lifetime of Moshoeshoe. Although men were less likely to convert, or to remain converted, many women did, including the senior wives of Moshoeshoe, followed by those of Letsie and Lerotholi. Women as such were at the forefront of the emerging spiritual, cultural and social (r)evolution.

From one generation to the next, the missionary enterprise expanded, with new institutions and associations that would make an ever-wider impact: Morija would grow from being a small settlement to become ‘Selibeng sa Thuto, Selibeng sa Tsebo’, the fountain of learning.

Matsieng: The centre of gravity shifts from Thaba-Bosiu to Makhoarane

The Basotho nation lost a great deal of its territory to the west of the Caledon during the wars of 1865-1868 with the Orange Free State. In order to prevent a complete debacle, Moshoeshoe requested the protection of Britain, which was granted on 12 March 1868. The founder of the Basotho nation, then well over 80 years of age, could rest assured that his people would survive. Moshoeshoe passed away on 11 March 1870, after which his senior son Letsie succeeded as Morena e Moholo. By then Letsie had left his previous place of residence at Morija to a point 7 km further up the valley at Ha Rakhuiti which became known as Matsieng.

Letsie faced two great challenges: i) the imposition of magistrates from the Cape Colony which took over the administration of Lesotho in 1871, and ii) the fact that his brothers Molapo and Masupha governed their districts with little regard for him, the same being true of Moorosi’s Baphuthi in the far south.

The colonial administration, though limited in terms of officials and security forces, proved to be quite effectual in limiting the power of the chiefs as the magistrates did their best to prevent abuses, thus gaining favour with a section of the population. This experiment, however, was completely undermined by the ‘Peace Preservation Act’ by which the Cape sought to disarm Basotho in 1880, as if ‘they could not be trusted’. The nation was badly divided, with Molapo and his son Jonathan favouring disarmament, together with many of the junior sons of Moshoeshoe, while Lerotholi, Masupha, Ramaneella and Joel fought against the Cape.

Ultimately, the ‘rebels’ were able to keep the Cape forces at bay, the stalemate leading to the withdrawal of the Cape from the administration of ‘Basutoland’ in 1884 and the territory reverting to direct administration under the British High Commissioner. Hence forward, the nation would be guided by a Resident Commissioner and officials whose task it was to support the chieftainship, and especially the central role of the ‘Paramount Chief’.

During the Gun War, Letsie had played a double game with the Cape, reaffirming his allegiance while ‘passively’ working against the ‘rebels’. Though the new British administration supported his central position from 1884, his health was now frail and the nation was more enthusiastic towards his son, Lerotholi. who was seen as a great hero in the Gun War.

The second challenge that Letsie faced was handled differently. During the 1870s, it was discovered that the sons of Molapo were quickly settling in the Malibamatso and Senqu river valleys deep in the mountains of the country, and had met with Baphuthi coming up from the south at what is today ha Makunyapane (in Thaba Tseka). Letsie (followed by Lerotholi) deployed his allies – especially the Bafokeng ba Khoele of his mother ‘Mamohato’s people – and his sons to take control of these mountainous areas. A major move in this regard was the placement of Lelingoana’s Batlokoa in the upper Senqu basin to displace the Makholokoe of Lekunya, allied to Joel Molapo. This way, the expansive plans of Molapo’s sons and the Baphuthi were greatly curtailed, with chiefs loyal to Matsieng/ Makeneng eventually taking over the entire Senqu river valley.

Makeneng, the village of Lerotholi, was established in 1892 after the death of Letsie I. Situated at the top of a small plateau mid-way between Matsieng and Morija, this Royal Village, largely unknown today, presents a magnificent panorama and has much to offer visitors and tourists. Then home to Lerotholi’s 68 wives, some of its most notable architectural features have endured, crafted expertly by Basotho artisans, graduates of Leloaleng Trade School in Quthing, led by Gideon ‘Qebe’ Seboka

More Complex Challenges and Contrasting Visions of Development

Forged in the time of war, Lerotholi was the last of the Heroic Age. Threatened from without and later from within, the greatest challenge was to maintain the integrity of Moshoeshoe’s legacy. During the time of Lerotholi’s son, Letsie II (1905-1912), the unique position of ‘Basutoland’ was secured, surrounded as it was by the newly-formed Union of South Africa.

Though the Union would try on a number of occasions to incorporate Basutoland over the following four decades, Basotho remained firmly opposed to the possibility because both the ‘Colour Bar’ and later Apartheid would have made their future even less secure. Letsie II built his royal village at Phahameng, just to the east of Morija.

Lerotholi had worked so hard to see the codification of various laws (Laws of Lerotholi) endorsed during his lifetime so that his wayward son, Letsie II, could succeed him. Yet Letsie II was a hopeless drunkard, and spent most of his time with Bookholane, the very junior but beautiful wife of Letsie I, his deceased grandfather. Letsie II passed away quite prematurely in early 1913.

Griffith Lerotholi, the younger brother of Letsie II, then assumed the Paramountcy. Instead of serving as Regent till the son of his brother came of age, Griffith intended to sit on the throne ‘with both buttocks’. He was also the first Royal to convert, in this case to the Roman Catholic Church. This gave a new direction to the Monarchy and to the nation as the Oblates of Mary Immaculate poured resources into the country, such that by the 1940s, they came to surpass the previously well-established PEMS / Protestant Church of Basutoland. Griffith located his village below that of his grandfather Letsie I at Matsieng, from which location (New Matsieng) all subsequent monarchs have resided.

Once the external threats were minimised and central leadership from Makhoarane had re-assumed control of the country, the other key imperative was the health, prosperity and development of the nation. This challenge became increasingly difficult during periods of rapid change. Population growth, overploughing and overgrazing, and the constant bickering between chiefs over territory led to a scenario where Basutoland became a net importer of foodstuffs from the 1920s after previously serving as a bread basket for the region. As a result, i) increasing numbers of men (and women) sought a better life in South Africa, whether in terms of migrant labour or permanent residence; ii) a number of local movements arose to criticise chiefly abuses and to seek various remedies thereto, some even calling for greater democracy, while others opposed what they perceived as the growing ‘collusion’ between the chiefs, the churches and the colonial administration to undermine local values and traditions; and iii) the greatly deteriorating situation in the 1930s led to a more interventionist colonial administration that finally heeded the pressure and some of the advice of internal reform movements.

Griffith was succeeded by his son Seeiso in 1939, but Seeiso died relatively soon thereafter (late 1940). His wife, ‘Mantšebo, became Regent for the next 20 years. She was a complex figure, crying pitifully as a weapon she used against British officials, but expecting Basotho to call her ‘Ntate’ (Father, Sir) because ‘no woman has held such power’. When the now-mature son of Letsie II, Makhaola, continued to make noise that he was the rightful heir, she had the fine stone house of Letsie II at Phahameng torn down, stone by stone, symbolic of the utter demise she wished upon that family.

Griffith was succeeded by his son Seeiso in 1939, but Seeiso died relatively soon thereafter (late 1940). His wife, ‘Mantšebo, became Regent for the next 20 years. She was a complex figure, crying pitifully as a weapon she used against British officials, but expecting Basotho to call her ‘Ntate’ (Father, Sir) because ‘no woman has held such power’. When the now-mature son of Letsie II, Makhaola, continued to make noise that he was the rightful heir, she had the fine stone house of Letsie II at Phahameng torn down, stone by stone, symbolic of the utter demise she wished upon that family.

Regent ‘Mantšebo eventually gave way in 1960 for Moshoeshoe II to take the throne, his fortunes being decided before he really had any say in the matter. He would be a constitutional monarch, with merely symbolic powers, yet he foresaw that the rise of political parties was so divisive that these would tear newly independent Lesotho apart.

The Present Day

2016, the 50th Anniversary of Lesotho’s Independence from Britain, was a sombre and sober moment, less of celebration and more one of reflection and self-examination. 2024, the 200th Anniversary of the arrival of Moshoeshoe and his people at Thaba-Bosiu, may be another moment, perhaps more forward looking if at all the National Reforms process and other initiatives succeed to re-set the clock, re-calibrate the system and give our people hope for a better future.

During the 1950s, various debates were held about the future of the Basotho nation? Would it:

- continue to be ruled by an executive monarch, with power still largely placed in the hands of chiefs, the mainstay of traditional authority, tempered by councillors, a small civil service, churches, and traders?

- evolve to become a constitutional monarchy, with power largely in the hands of elected leaders, either under a system of tiers from district to national representative bodies, or through direct elections under a network of political parties?

- evolve to become a republic, and jettison all ties with traditional authority?

- craft a hybrid model to meet the nation’s needs and aspirations?

Since then, other possibilities have arisen:

5. throw in its lot and become a part of a liberated South Africa or federation of Southern Africa?

6. look forward to the break up of South Africa and carve out / craft a new larger state within the vacuum left.

Various voices have been raised over the intervening years. What is perhaps most striking however is the massive growth of the civil and security services, the diminishing role accorded to chiefs and churches, the proliferation of political parties, the growing loss of confidence in party political leadership, the ever increasing co-dependence of Lesotho’s destiny with regional and international bodies, the growing inequality in terms of wealth and opportunities, and the urgent need to address the plight of youth who, from 2012, have found their fortunes ever more precarious. Let us also remember that these challenges do not face Lesotho alone. South Africa, liberated South Africa, now has rolling blackouts (load shedding) and its water problems become ever more acute. After all, insecurity and rampant corruption are local, regional and global issues.

What then of the Legacy of Moshoeshoe? Or the Legacy of Makhoarane? We have seen that our monarchs are real people with strengths as well as weaknesses. So also other forms of leadership. In a short narrative, we have only been able to give a minimal amount of detail in this regard. Much more could be said, and needs to be said. A few points might be made, however:

- Leadership based purely on heredity (1st son of the most senior family) is inadequate, especially in times of great trial and tribulation;

- Electoral Democracy without accountability or relative stability and security is no solution;

- Leadership of whatever kind must be accountable to the people;

- Life evolves and institutions (family, chieftainship, churches, business, government) must adapt or lose relevance;

- Internal leadership faces pressures from below, as well as pressures from without – no nation is truly ‘sovereign’ in the sense that it can choose any path it wants.

The fact that history is not taught in most schools, that even what is taught may be simplistic, leaves us as a people with a poor perception of what is truly possible. Politicians promise us the sky even when the Treasury has no means of fulfilling such promises. When the truth dawns on us, we become disillusioned.

Makhoarane, the brooding mountain, has witnessed the rise and fall of kings, the spiritual inspiration and cultural interface with the baruti ba Moshoeshoe (of different denominations), the establishment of institutions that have had a far-reaching impact across the nation and regionally, the creative outpouring of (among others) a Thomas Mofolo, a ZD Mangoaela, and a JP Mohapeloa, and more recent initiatives like the Morija Arts & Cultural Festival, and now the Seriti sa Makhoarane Heritage & Tourism Network (SSM).

SSM is a community-based network committed to developing the tourism value chain in the greater Morija-Matsieng area based upon enhanced preservation, presentation and promotion of its key heritage sites and resources. Makhoarane has a wealth of history, heritage sites, living culture and creativity to share with Basotho and the wider world.

Makhoarane, long celebrated in song, will continue to make an impact as Basotho re-appropriate certain aspects of their broader traditions while adapting others so as to enhance their sense of botho (fuller humanity) so that both individually and collectively, a more hopeful and stable future can dawn, one that even Moshoeshoe the Great would appreciate and commend. Khotso, ha e ate!